This is the third field diary entry from Paz, one of our Digital Identity Fellows. Her year-long research project is focused on unravelling what digital identity, and identity in general, means to the unemployed and under-employed individuals receiving support from public job centres and local labour organisations in Gran Buenos Aires and Mar del Plata in Argentina.

*****

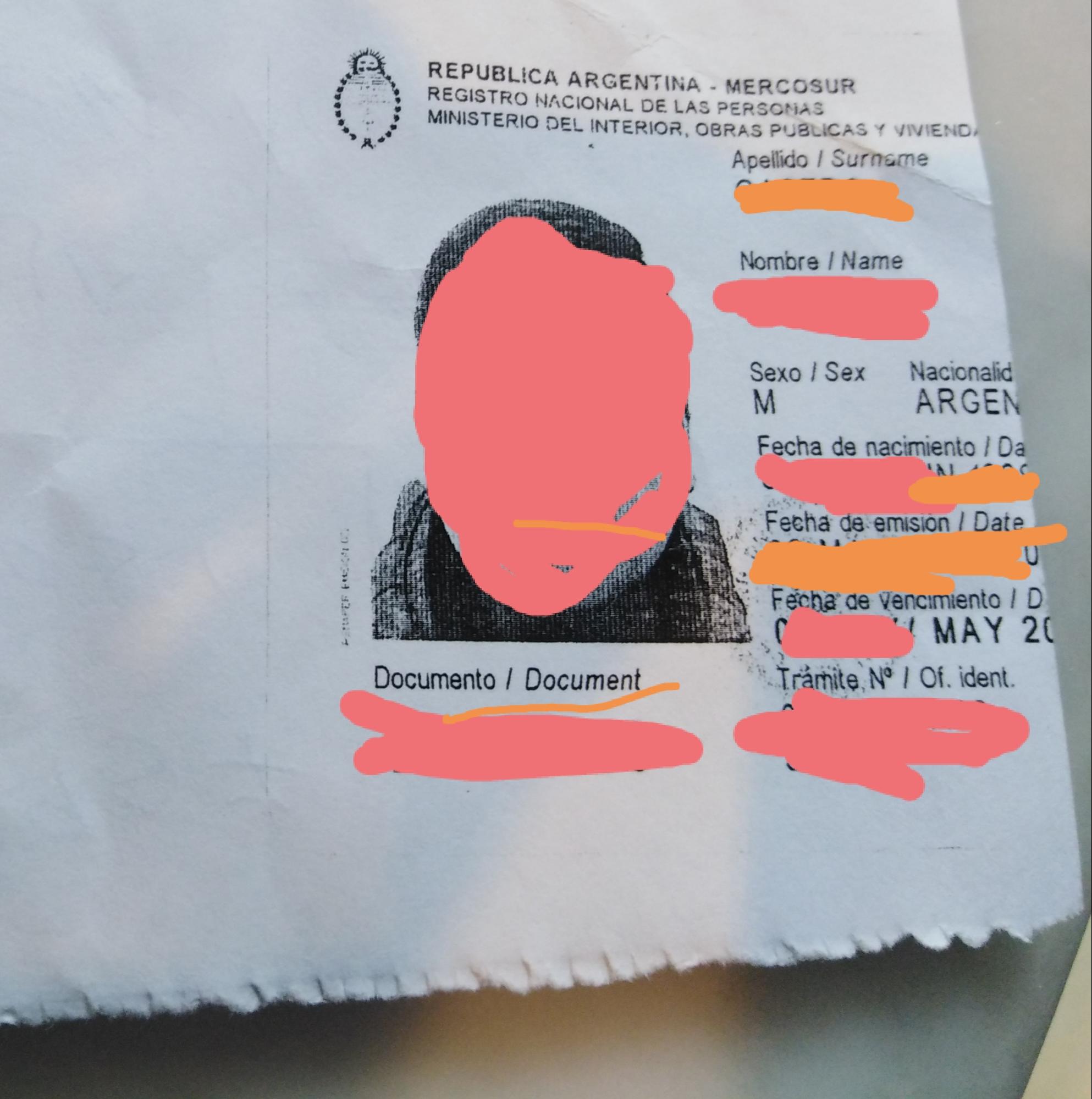

The image at the top of this article is a photo I took of a piece of paper with some phone contacts I was given at a public job centre office. They had ‘recycled’ people’s ID photocopies. I walked away with all the personal data of a person I didn’t know.

When conducting interviews, I try to avoid defining identity or digital identity. Providing definitions, at least at the beginning, might create a barrier with the interviewees, some of whom might suspect that “I am an expert and I only want you to confirm what I already know”. I do not want such a barrier, precisely because of the exploratory nature of my research; the knowledge I am looking for is in the interviewees. This is the case with all the interviewees, including those with no formal technology background whatsoever, or those with vulnerable backgrounds, or those looking for a job. More often than not, however, I am being increasingly asked for a definition. My response has been to paraphrase definitions in ways that can be easy to grasp, and which are also relatable and open enough so that people can be confident that their own knowledge and experiences are relevant.

I am doing my fieldwork in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and a full-scale quarantine in Argentina. My interviews are now conducted online or over the phone, which makes it even more important for my narrative to be compelling and to elicit a nuanced conversation (that doesn’t end up turning into COVID-19 coping strategies).

In this post I’ll first provide the formal definitions, and then the informal ones I am mostly using during interviews.

Key concepts

Identity

I do not provide a clear-cut definition, and I believe I am excused for this because identity is too much of a complex and ever changing concept. As Florian Coulmas rightly explains:

“Individual identities are complex structures combining inherited features with various group memberships, loyalties, values, belief systems, and fashions. These structures adjust to changing circumstances and so does the concept of identity itself. Elements may be discarded or remixed, new ones added on occasion. Hence a definitive definition is not available”.

Despite the lack of an all-encompassing definition (as explained, for example, by Aleks Krotoski and Ben Hammersley in Identity and Agency) there is a list of things ‘identity’ might refer to:

- the way one is recognized as an entity;

- how we define and express our self individually or collectively;

- the sum ownership of the tangible and intangible assets of the self;

- and the sum of self-referential claims or claims about others made by a digital subject (a concern for computer science).

Digital identity

Related of course, but different from ‘identity’, ‘digital identity’ seems a little less complex in that it refers to ‘all of the above but in a digital format’. Or perhaps not. According to Krotoski & Hammersley, digital identity can be defined as:

“A set of data that acts as a unique reference to a specific object”, which “can be a person, a thing, a concept, a group, or any other definable entity”.

Digital identity’s main role is authentication: verifying whether an entity is who (or what) it is believed to be, and worthy of trust. And in the case of digital identity this authentication is binary: either completely true or completely false.

A digital identity relating to a person can be made up of a number of attributes (data) depending on what it is needed for, and could include one or more of: an email address, digital photos, usernames and passwords, biometric data, or any other information that can be accessed digitally (Yoti toolkit).

Our email address, for example, can be our digital identity within a specific email system, but it can also work as the digital identity we have on another, unrelated service (Krotoski & Hammersley) (like another platform for which we use our email to sign in).

Your digital identity can be verified using documents or other data such as biometrics or identification credentials, which can confirm you are who you say you are, in legal terms. But not all of our digital identities need to be verified in this way, only those that might be used to access services from governments (e.g healthcare) and the private sector (e.g banking).

Online identity

Then we have a third, and equally relevant concept: ‘online identity’:

“While digital identity answers the question, ‘Are we sure that x is y?’, online identity continues the statement, ‘I, y, consist of a, b, and c’.” (Krotoski & Hammersley).

Online identity relates closely to the offline definition most of us have of personal identity or self-identity: it is the expression of this self-identity as mediated by computers and the internet. And importantly, this expression necessitates editing, a process that is culturally and technologically constrained (or limited):

“Online identities are not limitless in their expressive abilities. Unlike the self-signals shared between strangers on the street, each identity marker on the web is proactively constructed using the tools available, and online identity is not without systems and structures that constrain the individual, both socially and technologically” (Krotoski & Hammersley).

The use of a tool to build an online identity (for example, a profile on Facebook) reduces our ability to decide which parts of our online identity(ies) we want to express, and how we want to express them. The choices, and therefore agency, are really in the hands of the designers of the platforms; choices that are political and cultural. We do not have the control we are often told we have. The designers of online services directly define the way we build our online selves.

Digital identity and our fluid online identity

As seen, digital identity is necessary to an online identity, but they are not the same:

“Digital identities are fixed and binary; online identities are fluid, and contain multitudes” (Krotoski & Hammersley).

The social sciences have long considered an individual’s self-concept as an evolving process, in which we discard aspects that no longer fit us in a given context (Krotoski & Hammersley). This ability to include and discard, allowing our identities to evolve, is essential to what we call ‘agency’. The more constrained we are to do that, the less ‘agents’ we are. The problem is: “the nature of some contemporary constructions of digital identity (notably, for search or social networking applications) does not account for this evolution. Rather, it incorporates all aspects of the self (self-reported or algorithmically generated) and delivers it upon request”. Identities are treated as trackable, unchanged, stable. Thus the need to incorporate the nuances of our experiences into computer constructions of identity (Krotoski & Hammersley).

Such ‘nuance’ might prove even more vital during the processes of editing our online identities, and creating new digital identities, when looking for a job. Among vulnerable groups such editing might be crucial, as career/training paths are not the ‘traditionally expected college-graduate-school’ and discrimination takes place regarding issues such as where people live, where they went to school, what their technical qualifications are, and so on.

The word “Respect”, written by adults and young adults at CEPLA, also called Casa Caracol, a community center in Mar del Plata

My narrative during interviews

At the start of my interviews I provide many of these same definitions, but make them a little less formal:

- Identity is something complex, yet we all know what our identities are. We know they relate to things we cannot change (like the country or social group we were born into), but also to other things that can change, like our values and beliefs that change over time. There is sameness, but also difference. We are and are not our 5 year-old self. It is a complex concept we all need to grasp.

- Digital identity is something rather different. Digital identities exist because we also live in a digital world. A digital identity is a set of data that defines a specific object: a person, a group or any other thing. This data, or digital identity, is only used to verify someone or something is who or what it says it is; the answer can only be yes or no. There are no in-betweens. When entering Facebook, for example, you are required to verify you are “Paty X” by entering your username (which is your email) and a password. So, in this case your digital identity on Facebook is made up of two attributes, your username and your password. If you enter the wrong password the system determines that you are not Paty X. Period.

- Online identity, on the other hand, refers to our ‘fluid’ or changing identities: it is not about “are you or not who you say you are?”, but more of “yes, I am Paty and I am also this and that, extrovert and artist, activist and organizer, and I currently maintain a Facebook page about sharing tools we don’t use too often with our neighbours”. Our online identities are the expression – in the digital world – of our offline and nuanced identities.

So far, interviewees have added a lot more nuance to the digital identity and online identity definitions. This proves that providing simple and informal definitions can help set the stage for a discussion without competing against – or overshadowing – the interviewees’ own understandings. One example of such nuance refers to the fact many people share their digital devices with other people, often family members. More on this in future posts.

Lastly, just to mention: in order to compensate for the lack of in person clues or contextual information during the now-online interviews I am adding two research methods: photo/video/voice elicitation and story completion, which I will also describe in more detail in another post.